Ce petit village s’appelle Kilmarnock. Il se situe à quelques kilomètres d’Irvine et héberge les Trashcan Sinatras. A l’écart de Glasgow et des lumières, les Trashcan Sinatras ont bâti, en quasiment trente ans d’existence une discographie exemplaire. La presse anglo-saxonne en parla un peu, la presse française encore moins. Emmanuel Tellier (druide de la tribu Les Inrockuptibles) prit son bâton de pèlerin et rendit visite à nos quatre génies en pleine folie Brit Pop. Après ça, on oublia totalement les TCS. On compte quelques chroniques disséminées à droite et à gauche. Pour laver ce bien triste affront, nous avons demandé à Francis Reader de commenter la discographie de son groupe. On découvre, à travers ses mots, un groupe qui débuta comme voisin de palier des La’s et qui a résisté à toutes les embûches que le destin lui a semé.

Cake

Cake est le premier album du groupe et a fini à la 74ième place des charts anglo-saxons. Publié en 1990, Cake défend les Byrds alors que l’Angleterre ne pense qu’aux Happy Mondays.

Comment avez-vous rencontré Go! Discs ?

Francis Reader : Nous commencions juste à écrire nos propres chansons quand nous avons envoyé des cassettes aux promoteurs de Glasgow et d’Édimbourg pour essayer de décrocher des concerts dans ces villes en tant que tête d’affiche ou pour assurer des premières parties. Nous avons eu une réponse positive d’un de ces promoteurs appelé. Il s’agissait de Dance Factory et il nous a permis d’ouvrir pour les Lilac Time. Nous avons tourné avec les Lilac Time. Lors de ces concerts, nous avons rencontré Simon Dine qui était un fan des Lilac Time… Mais aussi leur roadie et leur attaché de presse. Il travaillait aussi comme directeur artistique pour Go! Discs. Il a aimé notre groupe et nous a recommandé à la direction du label. A cette époque, c’était un petit label qui avait juste Billy Bragg, les Housemartins (qui allaient bientôt disparaître) et les La’s qu’ils venaient de signer si je me rappelle bien. Ils venaient de signer un contrat de distribution avec Polygram donc ils avaient de l’argent à perdre. Ils ont décidé de nous faire une offre pour un contrat et nous l’avons acceptée. Nous aimions les gens de ce label et nous avons passé de bons moments avec eux. Nous passions tout notre temps là bas à une certaine époque. Ils nous apporté une certaine forme de souplesse.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Mdhvm3r4ALQ

Et pourquoi avoir acheté de suite un studio ? Vous étiez un très jeune groupe.

Francis Reader : Pendant quelques années, avant de signer sur Go, j’ai travaillé comme ingénieur, faiseur de thé, promeneur de chiens dans un studio appelé Sirocco. On y enregistrait surtout de la musique traditionnelle écossaise avec des accordéons et des cornemuses. Le propriétaire me laissait enregistrer des démos avec mon groupe la nuit. Nous connaissions donc bien cet endroit et nous aimions l’utiliser. Nous avons signé un contrat et nous avons touché une avance confortable qui nous a permis d’acheter notre propre studio pour y enregistrer nos disques. Nous avons donc changé le nom et nous l’avons appelé Shabby Road. Nous avons remplacé les cornemuses par nos Rickenbackers et nos posters des Jam et des Beatles. Nous y avons enregistré trois albums. Était-ce la bonne décision ?

Cela a été un peu difficile quand nous avons dû resserrer les écrous et les boulons pour garder cette maison étanche et correctement chauffée. Finalement nous avons fait faillite et nous avons dû nous en séparer. En même temps ce n’était pas plus mal. Nous y passions tellement de temps… Nous avions perdu le fil de notre vie. Mais cela a quand même permis de créer de bons souvenirs et de bonnes chansons.

Quels sont tes meilleurs souvenirs de l’enregistrement de ce disque ?

Francis Reader : J’aime bien me souvenir de nos enregistrements analogiques. Nous utilisions des magnétophones, un grand bureau et nous avions pas mal d’espace pour tirer des câbles et faire des montages de micros. Ergonomiquement, c’était juste une manière très agréable de travailler sur les différentes couches et les chansons. En comparaison, je trouve que travailler sur un ordinateur est très insatisfaisant et contre-intuitif. Nous avions appris à connaître les murs, les tapis et les chats… Comment travailler avec des toilettes capricieuses, quand répondre ou ne pas répondre quand quelqu’un frappait à la porte. C’était notre maison, elle faisait partie de nous et son caractère a semblé s’infiltrer dans la musique que nous avons faite en son sein. Je visualise encore l’endroit quand j’entends des chansons qui ont été enregistrées là, y compris ceux d’autres groupes qui l’ont utilisée. Et je sens toujours l’odeur des besoins du chat.

C’était votre premier album. Avez-vous des regrets ?

Francis Reader : J’aurais certainement des regrets si je me l’autorisais. Mais à quoi bon ? C’est ce qu’on appelle un enregistrement parce que c’est un enregistrement de ce que nous étions tous à l’époque, pour le meilleur ou pour le pire, et rien ne changera cela. Je n’écoute jamais Cake. C’est une bonne indication. La seule chose qui compte est d’avoir été fidèle à ses propres idéaux. C’est naturel de changer et de devenir de se voir comme un étranger. Nous ne pourrions pas enregistrer Cake aujourd’hui. Impossible !

I’ve Seen Everything

I’ve Seen Everything a été publié en 1993 et est le seul disque du groupe a accrocher le top 50 anglais.

I’ve Seen Everything a été publié par London Records. Pourquoi avoir quitté Go! Discs ?

Francis Reader : Non, non, nous n’avons pas quitté Go! Discs. London Records était utilisé par notre label pour publier des disques en dehors du Royaume-Uni. Nous sommes restés avec Go! Discs pour ce disque et le suivant.

Pourquoi avez-vous choisi Ray Shulman comme producteur ?

Francis Reader : Mes souvenirs sont un peu vague. Notre goût pour le post-rock commençait à être découvert quand nous nous sommes mis à fumer de l’herbe et à boire moins d’alcool (aujourd’hui, nous buvons toujours autant d’alcool et nous fumons toujours autant) mais je ne me rappelle pas qui a évoqué le nom de Gentle Giant. Nous avons tenté de faire produire I’ve Seen Everything par Steve Lillywhite mais il n’était pas intéressé alors nous l’avons fait nous-même. Il nous a dit qu’il essayait d’arrêter de faire des productions et qu’il voulait travailler pour Go! Discs en tant que directeur artistique. Nous n’avions pas assez de chansons terminées et il n’était pas intéressé par le fait de nous cajoler et nous en avions vraiment besoin. Le nom de Ray est venu comme ça et nous l’avons rencontré. C’était en effet un géant doux, gentil, drôle, talentueux et il semblait savoir instinctivement comment nous cajoler, nous détendre et se moquer de nous. Il était heureux de venir à Kilmarnock pour travailler sur l’album à Shabby Road, tant que nous logions dans l’hôtel le plus cossu de la ville et tant que nous n’applaudissions pas l’équipe d’Angleterre qui jouait l’Euro. Je me demande où il est maintenant. Je voudrais bien le saluer.

Pourquoi l’avoir appelé I’ve Seen Everything ?

Francis Reader : L’album devait s’appeler Spooktime mais j’ai reçu un coup de téléphone du boss de Go ! Discs quelques temps avant que la pochette du disque ne soit imprimée et il m’a dit que la division américaine du label avait eu vent de notre idée de titre et qu’ils n’étaient pas contents de l’utilisation du mot « spook » car c’était un mot à consonance raciste. Nous ne le savions pas (on pensait que cela voulait dire ‘fantôme’) et nous ne voulions passer pour la branche écossaise du Ku Klux Klan et nous avons donc changé le titre. Le problème c’est que nous n’avions que très peu de temps. Nous avons donc pioché dans les paroles des chansons de l’album pour trouver quelque chose qui fonctionne. Si je me rappelle bien, le titre vient des chansons The Hairy Years et I’ve Seen Everything. Tout cela c’est fait très rapidement. Nous aurons dû peut-être trouver un autre titre.

Quelle est l’histoire de la chanson Hayfever ?

Francis Reader : Nous l’avons écrite ensemble. Paul a écrit la musique et la mélodie. John, Davy et moi nous sommes assis ensembles avec nos cahiers et une paire de ciseaux pour écrire les paroles. C’était un exercice d’image de mot vraiment, basé sur un amalgame de personnages mâles inégalables – une rancune contre ce que nous appelons à juste titre aujourd’hui « masculinité toxique ». Ray Shulman a aussi beaucoup aidé. La chanson était en morceaux quand nous l’avons tout d’abord amené dans le studio – assez tard dans l’enregistrement de l’album – mais il a trouvé un moyen de rassembler les parties dans ce que vous entendez aujourd’hui. C’est probablement là que sa vie passée prog-rock fût très pratique. Je pense qu’il a écrit l’arrangement de Hayfever.

Trashcan Sinatras – Hayfever

Comment avez-vous rencontré Nick Ingham ?

Francis Reader : Grâce à Ray Shulman ! Je ne me souviens de rien à propos de Nick. Tout à l’heure, j’ai regardé la liste de ses clients sur son site Internet… il ne se souvient pas de nous non plus. Néanmoins, il a fait un beau travail sur Hayfever et un arrangement vraiment fabuleux, notamment sur la chanson Easy Read. Cela a propulsé cette chanson de la dernière place à la première !

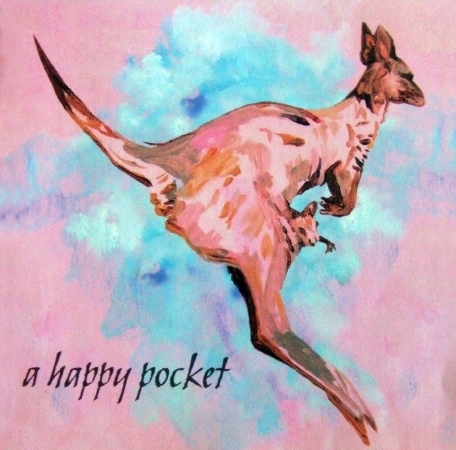

A Happy Pocket

Dernier disque chez Go! Discs, A Happy Pocket est considéré comme un des meilleurs albums du groupe. Publié en 1996, ce disque est le grand oublié de cette période alors qu’il contient de merveilleuses chansons.

Pourquoi avoir appelé ce disque A Happy Pocket ? pourquoi avoir choisi cette pochette ? pourquoi avoir mis une carte au dos du disque ?

Francis Reader : « Une poche pleine est une poche heureuse » était une phrase de Michael O’Donnell notre ingénieur son du temps de l’album Cake. Il disait ça quand il touchait son salaire. Quand il est mort, nous avons voulu lui rendre hommage et cette phrase nous est venue à l’esprit. A Happy Pocket est fait pour toutes ces personnes qui travaillaient pour nous. Nous n’étions pas toujours heureux… Cela peut se voir avec la version française de notre album car on peut dire « Un Happy Pocket ». Pour la pochette, nous avons fait une commande à une amie. Nous lui avons demandé de nous peindre quelque chose uniquement inspiré par le titre. Elle a fait cela. A noter que c’est le détail d’un tableau bien plus grand. La pochette arrière était juste une idée comme ça. Nous voulions présenter la liste des chansons d’une manière plus romanesque – ou plus ennuyeuse. Vous essayez toujours de plier ces cartes… Un ami m’a dit qu’il est entré dans la seule boutique de disques de Kilmarnock le jour où l’album est sorti. Le disquaire était ravi car il a vu le nom de la ville au dos du disque : « Les garçons ont mis l’endroit sur la carte ! »

Pourquoi avoir quitté Go ! Discs ?

Francis Reader : Nous n’avons jamais quitté Go ! Discs. C’est peut-être une version française du disque.

Pourquoi avoir vous même produit l’album ?

Francis Reader : Nous n’avons pas pris une décision consciente de produire nous-mêmes, nous avons juste accumulé beaucoup de chansons pendant des jours et des nuits en enregistrant des chansons à Shabby Road. Elles étaient surtout très bien enregistrées, car à cette époque, nous travaillions en studio avec un excellent ingénieur qui s’appelait Larry Primrose. Nous étions toujours là – soit le groupe entier, ou dans les uns et les deux. Il n’était pas nécessaire d’appeler n’importe qui jusqu’à ce que les chansons aient atteint l’étape du mix. A cette époque, notre amateurisme faisait de nous des gens très responsables. Nous avons mixé les chansons avec Cenzo Townshend et Steve Whitfield, tous deux venus travailler à Shabby Road et avec Hugh Jones, qui nous a emmenés au Wool Hall de Bath pour travailler pendant l’été. Nous lui serons toujours reconnaissants.

Comment avez-vous trouvé le son de cet album ?

Francis Reader : Il y a beaucoup de dulcimer, de 12 cordes acoustiques. Mais le disque n’est pas aérien pour autant. Les sons semblent un peu menaçants et donnent une impression de claustrophobie. J’aime ça. Il résume bien l’humeur du groupe à cette époque. Nous étions méfiants et fatigués.

Quels sont tes meilleurs souvenirs liés à cet enregistrement ?

Francis Reader : Le temps passé au The Woll Hall furent charmants. Le temps estival en Angleterre, quand nous avons un été, est si beau… Nous n’avions pas vraiment besoin de tout ça en studio parce que c’était surtout une séance de mixage, alors je me suis promené dans le village, j’ai assisté à quelques sessions de Dancing Morris dans le pub et bu pas mal de cidre. J’ai beaucoup bu en fait, mais je suis aussi allé me faire pardonner à l’église locale. Il n’y a donc aucun souci. C’était comme si nous étions de retour dans les années 1930… Sans la guerre imminente.

Quelle est ta chanson préférée de ce disque ?

Francis Reader : J’aime la chanson instrumentale Outside. J’ai toujours préféré écouter les versions instrumentales de nos chansons J’aime toujours The Genius I Was. Et qui ne pourrait pas aimer entendre Paul chanter sur I Must Fly ? Safecracker est aussi une excellente chanson.

Trashcan Sinatras – The Genius I Was

Weightlifting

Après une pause de 8 ans, les Trashcan Sinatras mettent les voiles vers New-York et enregistrent Weightlifting chez Andy Chase.

Comment avez-vous rencontré Simon Dine ?

Francis Reader : Nous avons parcouru un bon bout de chemin ensemble. Il était présent sur la tournée des Lilac Time en 1988 et nous a vu faire les premières parties à Édimbourg et à Dundee. C’est lui qui nous a fait signer chez Go! Discs. Il a travaillé avec nous jusqu’à son départ du label. Il est parti avant la sortie de A Happy Pocket si je me souviens bien. À ce moment-là, lui et moi étions devenus des amis proches, et quand il a commencé à faire sa propre musique (avec Noonday Underground), j’ai vraiment aimé ce qu’il faisait et je lui a demandé de venir à Shabby Road pour travailler sur le mix de son premier album (Self Assembly) avec lui. Puis j’ai écrit et chanté sur quelques chansons de son deuxième album (Surface Noise). Il a fait quelques disques pendant que nous enregistrions Weightlifting. Je lui ai demandé d’essayer de travailler sa magie sur un couple de nos airs.

Norman Blake (Teenage Fanclub) chante sur Got Carried Away. Quelles sont vos influences sur Weightlifting ? Le Teenage Fanclub en fait partie ?

Francis Reader : C’est difficile de te répondre 15 ans après. Mais je me rappelle que nous étions très déterminés. Nous venions de quitter notre maison de disques dans des conditions désastreuses… Mais nous avons réalisé que nous étions assez résilients en tant que compositeurs. Savoir que nous pouvions encore nous faire plaisir était rassurant.

Comment vous êtes vous retrouvés sur SpinART Records ?

Francis Reader: C’est notre manager qui a trouvé ce label en pensant que ce serait une bonne rencontre. Malheureusement il n’en fut rien. Nous attendons toujours le versement américain de nos droits d’auteur de Weightlifting<. Nous ne les avons jamais touchés.

Comment écrivez-vous vos chansons ? Vous utilisez toujours la même méthode ?

Francis Reader : Certains aspects de notre méthode sont toujours les mêmes. Paul et moi écrivons beaucoup ensemble, comme Davy et moi. John a tendance à écrire de son côté. Cela dit, nous sommes tous conscients que les chansons ont besoin d’idées, et chacun membre du groupe exprime toujours ses opinions. Tout cela se faisait en face-à-face, et maintenant tout se passe par mails (Paul et moi vivons aux États-Unis, John et Davy sont toujours en Écosse). Ce changement a ralenti les choses, mais c’est la façon dont les choses devaient se faire.

Mais au final, pourquoi vous êtes-vous appelés The Trashcan Sinatras ?

Francis Reader : C’est une vieille histoire. Les quatre membres originaux du groupe sont Davy Hughes, George McDaid (qui jouait de la basse sur Cake), un batteur appelé Paul Forde et moi même. Nous nous sommes rencontrés lors d’une formation à la mission locale. A cette époque, nous étions au chômage. L’un des objectifs de cette semaine était de monter un spectacle. Les trois autres évoluaient dans différents groupes. Moi non… Nous avons décidé de monter un concert et de jouer de la musique en utilisant ce que nous pouvions trouver à la poubelle. Nous avons rassemblé des choses à frapper, des choses à souffler (après les avoir nettoyées), et Davy a chanté une chanson de Frank Sinatra. Paul Forde a inventé le nom, et quand nous avons décidé de jouer un vrai concert quelques mois plus tard, nous nous sommes accrochés à lui. Le groupe a évolué assez rapidement, et je pense que nous avons grandi dans le nom musicalement, en ce sens que nous avons toujours aimé combiner nos inclinations punk avec notre amour collectif du Tin Pan Alley.

In The Music

In The Music prolonge l’aventure américaine des Trashcan Sinatras. Célébré par la presse anglaise, ce disque est accompagné d’une tournée mondiale.

Comment avez-vous rencontré Andy Chase ? Et Carly Simon ?

Francis Reader : Andy nous avait rencontré pour nous proposer de faire le mix de Weightlifting. Il avait fait du bon travail, nous lui avons donc proposé de travailler sur le disque suivant. Quatre ans plus tard, nous avions assez de bonnes chansons pour aller le voir dans son studio à New York. Carly était sa voisine. Nous avons rencontré Andy quand nous avons enregistré les voix de l’album à Martha’s Vineyard. Quand nous nous sommes aperçus que nous avions un lien l’immense Carly Simon, nous nous sommes mis en tête de l’inviter à chanter sur une de nos chansons. John lui a écrit une lettre et y a joint une cassette avec des chansons. Elle nous a répondu. C’était fantastique ! Elle aimait bien la chanson de John intitulée Should I Pray ?. Ce fut un grand honneur pour nous, surtout pour John. Nous n’avons pas pu la rencontrer malheureusement. Cela aurait été trop demander.

Trashcan Sinatras – Should I Pray ?

Quelle est l’histoire de Morning Star ?

Francis Reader : Je viens juste de l’écouter pour voir quels sont mes souvenirs. Je pense que la musique de Paul est vraiment bien. Je ne pense pas la même chose des mots que j’ai écrits et de ma voix. L’intégralité d’In The Music est marqué par la joie ce qui est difficile à verbaliser sans passer pour un blaireau qui se plaint. J’ai essayé d’écrire quelque chose qui évoquait ma vie. C’est venu de façon un peu maladroite. Ce n’est pas ma chanson préférée…

.

Comment s’est déroulé l’enregistrement ?

Francis Reader : Ce fut un délice du début à la fin. Nous avons recruté Grant qui joue de basse de manière très pétillante, Stevie – qui est toujours avec nous aujourd’hui – aux claviers, et Jody, un ami, a joué de la guitare, afin que nous puissions joueraie fête. Les journées furent longues et ponctuées d’accords et les nuits furent plonger danr les pistes de soutien en direct. Nous avons tous filés à Manhattan, au studio d’Andy Chase, et ce fut une fête. Les journées furent longues et ponctuées par les accords de guitare. Nous avons passé nos nuits dan un beau bar, le Dive Bar, et notre argent est parti dans son juke-box.

Vous avez fait une grande tournée pour défendre ce disque avec pas moins de 40 concerts aux États-Unis, au Japon, au Royaume-Uni… Quel est ton souvenir préféré ?

Francis Reader : Il y a certains endroits aux États-Unis où le public a tendance à être bruyant et à se faire plaisir. Les publics de Saint-Louis et de San Francisco me viennent à l’esprit. Détroit, aussi. Le Japon est toujours merveilleusement étrange. Un moment important de la tournée a été d’apprendre une chanson en japonais et d’avoir nos amis du Sunny Day Service de Tokyo qui se joignent à nous pour la jouer. Ils ont bien ri à propos de ma prononciation étranglée…

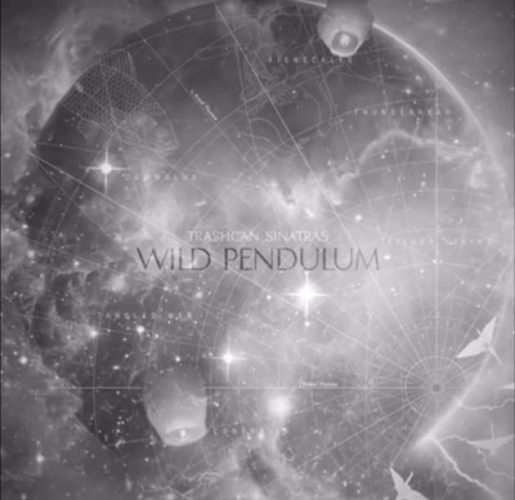

Wild Pendulum

Wild Pendulum est le chef d’œuvre du groupe.

Il s’agit de votre meilleur album. Je ne me trompe pas ?

Francis Reader : Il se pourrait bien que tu aies raison. C’est certainement mon disque préféré.

Quelle est l’histoire de All Night ? Cette chanson est totalement démente !

Francis Reader : Au départ, il s’agissait d’une chanson assez plaintive et jolie. John avait en charge le refrain et Davy et moi les couplets. En écrivant, je pensais à l’évolution de nombreuses églises de Glasgow. Elles sont assez anciennes et splendides. Certaines finissent par être transformées en boîtes de nuit. L’idée du DJ rédempteur qui prêche sur une chaire m’est venue ainsi… Je pense que Jésus approuverait. Nous l’avons envoyée à Simon Dine pour voir s’il aimerait ajouter quelques-unes de ses orchestrations dont il a le secret. Il est revenu avec ce que vous entendez (Lonely Bull d’Herb Alpert etc.). Je te reparle de Simon plus tard.

Trashcan Sinatras – All Night

Votre nouveau son est fantastique. Comment l’avez vous trouvé ?

Francis Reader : Tout est en lié à Simon Dine. Il a été notre directeur artistique chez Go ! Discs. Nous entendions bien et nous avions pensé faire un disque ensemble. Quand le moment est venu pour le groupe de rassembler nos énergies pour entamer l’ascension d’un nouvel enregistrement, nous avons constaté que nous n’avions pas de matière. Je me suis mis alors à écouter les dernières idées de Simon et j’ai trouvé cela fantastique et cela m’a beaucoup inspiré.

J’ai suggéré que tout le groupe se reforme et fasse ce disque avec Simon. Nous avions eu quelques chansons que nous avons donné à Simon pour qu’il les embellisse, mais la plupart des chansons sur ce disque ont commencé comme des chansons instrumentales. Puis nous avons ajouté des accords, de nouvelles sections, trouvé des paroles qui pourraient rendre justice aux sons. Tout cela a pris un certain temps, et nous avons fini avec des démos assez déchiquetées et effilochées qui avaient besoin d’avis extérieurs. Quelques producteurs se sont sauvés en hurlant quand nous leur avons présenté les démos, mais Mike Mogis de Bright Eyes pensait que tout cela était bizarre donc potentiellement très amusant à travailler. Il a amené Nate Walcott de son groupe, qui a joué dessus et arrangé toutes les cordes. Nous sommes tous allés au studio de Mike au Nebraska et tout a fonctionné de façon merveilleuse. Nous n’aurions pas pu souhaiter avoir de meilleurs collaborateurs. Le son du disque leur doit beaucoup.

Trashcan Sinatras - Wild Pendulum

Vous avez publié ce disque via Pledge Music. Quelle est ton opinion sur le crowdfunding ?

Francis Reader : Nous avions eu recours à une forme de financement participatif cinq ans plus tout pour In The Music. Entre-temps les choses se sont établies pour l’enregistrement, la fabrication et la promotion des disques. C’est rassurant d’avoir des fans qui te suivent et qui t’aident. Je préférerais que ce soit pas nécessaire mais c’est ainsi. C’est la vie !

Retrouvez tous les informations relatives aux Trashcan Sinatras sur leur site officiel.

English text

Cake

How did you meet the label Go ! Discs ?

We were just starting to write our own songs, sending demo cassettes out to promoters in Glasgow and Edinburgh to try and get a few gigs in the cities – either on our own or supporting name bands – and we got a positive response from one called Dance Factory, who invited us to play a couple of supports with The Lilac Time. Touring with The Lilac Time as a press agent/roadie/fan/friend was a guy called Simon Dine, who was also working as a part-time A&R scout for Go. He liked the group and recommended us to the head of Go, which was still a very small company at the time, with only Billy Bragg, The Housemartins (soon to disband) and The La’s signed up, as I remember. Anyway, they had just signed the label up to one of those major distribution deals (with Polygram), so they had some new money burning a hole in their pocket, and so the head guy called us up to offer us some of it, which we decided to take pretty much straight away. We liked them all as people, and enjoyed good times with just about all of the staff at some point throughout our time there. And they put up with a fair amount of pompous stroppiness from me, in particular. More about Simon Dine later…

Why did you purchase a recording studio ? You were a very young band !!

For a couple of years leading up to the group signing to Go, I’d been working as an engineer/tea-maker/dogsbody at a studio called Sirocco – mostly recording Scottish traditional music, with accordions, bagpipes etc. The owner let me use the place to record demos for my own band through the nights, so we were all really used to this place, and enjoyed hanging out there. We signed a publishing deal and got a fairly large advance and decided it would be wise to buy the studio and make our records there – partly because we couldn’t think of anything else to do with the money. So we changed the name of the place to Shabby Road, threw out the bagpipes and moved our Rickenbackers in, hung a few Beatles and Jam posters, and made three albums there. Who knows if it was the right decision? It was a bit of a drag when we had to get down to the nuts and bolts of keeping a large facility like that heated and waterproofed, and ultimately we did go bankrupt through not being able to keep it together, but at the same time we had all those endless days and nights writing music and recording, where we lost track of time and life, which resulted in some memorable times and some good songs.

What’s your best memory about this recording process ?

I really have a fondness for the memory of analogue recording, using tape machines and a large desk, and having lots of space dedicated to laying cables and erecting scaffolds of microphones. Ergonomically, it was just a very pleasing way to work on layering sounds and songs. I find working on a computer to be very unsatisfying and counterintuitive in comparison. We got to know the walls and carpets and cats, how to work the temperamental toilets, when to answer the door and when not to. It was our own home, we made it part of us and it’s character seemed to seep into the music we made there. I still visualize the place when I hear some songs that were recorded there, including those of other bands who used it. And I still smell the catshit.

It was your first record. Did you have some regrets about this album ?

I certainly would have regrets if i allowed myself to, but what’s the point? It’s called a record because it’s a record of who we all were at the time, for better or for worse, and nothing changes that. I don’t ever listen to Cake, if that’s any indication. If you know you were being true to yourself and making music you were really into at a point in time, that’s the only thing that matters. It’s only natural to change and to sometimes become a stranger to your old self. We couldn’t make a Cake now. No chance.

I’ve Seen Everything

I’ve Seen Everything was published by London Records. Why did you leave Go ! Discs ?

I’m not sure if you’re asking me that because you think we changed labels at this point, but we didn’t. The mercantile movers and shakers at Go must have had an agreement to release Go records through London outside the UK, but nothing changed from our standpoint. We were still at Go for ISE and the next album.

Why did you choose Ray Shuman as producer ?

That’s a bit hazy. Our collective prog-rock tendencies were starting to be uncovered as we started smoking more pot and drinking less alcohol (actually, we didn’t start drinking less alcohol – we just added the pot), but I don’t remember anyone mentioning Gentle Giant or playing their music. We aborted an attempt to make ISE with Steve Lillywhite because he just wasn’t that interested in what we were trying to do. Him telling us he was trying to get out of the production game and more into doing A&R work for Go Discs should’ve got our alarm bells ringing. We didn’t have enough songs completed, but he wasn’t interested in coaxing stuff out of us and we really needed help in that area. So Ray’s name came up and we met him. He was indeed a gentle giant – kind, sweet, funny, talented, with no self-aggrandizing agenda, and he seemed to know instinctively how to cajole us and relax us, poke fun at us. Also, he was happy to come up to Kilmarnock and work on the album at Shabby Road, as long as we got him a room in the tidiest hotel in town and didn’t root for the team England was playing in the Euros. I wonder where he is now. I’d like to say hello.

What’s the reason behind the title « I’ve Seen Everything”?

The album was supposed to be called Spooktime, but I got a phone call at home from the head of Go just before the sleeve was to be printed up, and he told me that the record company in the US had heard the title and were really unhappy with us using the word ‘Spook’, it being a somewhat antiquated racial slur. We hadn’t even considered that, of course (we were thinking ‘ghosts’) but didn’t fancy being thought of as the Kilmarnock branch of the Ku Klux Klan, so we were happy to change it. But we didn’t have much time, so we scoured the songs and their lyrics for something that would work as an album title. As I remember, it came down to two of the song titles, ‘The Hairy Years’ and ‘I’ve Seen Everything’. Toss of the coin. We should’ve went for the other one.

What’s the story of Hayfever ?

We wrote it all together. Paul wrote the music and melody, John, Davy and i sat around together with our notebooks and a pair of scissors to write the lyrics. It was a word picture exercise really, based around an amalgam of unlikeable male characters – a rant against what we today quite rightly call ‘toxic masculinity’. Ray Shulman also helped a lot. The song was all in pieces when we first brought it into the studio – quite late into the recording of the album – but he found a way of assembling the parts into what you hear today. This is probably where his prog-rock past life came in handy. I think he wrote the basic string arrangement on the spot, too.

How did you meet Nick Ingham ?

Through Ray Shulman. I can’t remember anything about Nick, and looking at the list of previous clients on his website just now, he doesn’t remember us either. Nevertheless, he did some lovely work on Hayfever and a really fabulous, swooping arrangement for Easy Read, propelling the latter to first choice for opening song on the album.

A Happy Pocket

What’s the reason behind the title « A Happy Pocket » ? And why did you choose this cover ? The back cover is a map ? Why ?

“A full pocket is a happy pocket” is a phrase our live sound engineer around the time of Cake, Michael O’Donnell, would say as he was paid his wages. After he died, we wanted to pay our own tribute to him, and that came to mind. A Happy Pocket of people fit our circumstances well, too – tucked away in the provinces, happily working away at our music. We weren’t always happy, mind you, but for those times one could refer to the French version of the album, Un Happy Pocket.

We commissioned a friend to paint something for the cover based on just the title, and that’s what she came up with – at least, the cover image is a detail from her larger work.

The back cover was just an idea we had to present the song list in a more novel – or more annoying – way. You’re always trying to bend the format of these things. A friend told me he walked into Kilmarnock’s only record shop the day the album was released and the owner was smiling wide, holding up the back of record, and he said delightedly, “The boys have put the place on the map!” So take that, Johnnie Walker!

Why did you publish this album via Go ! Discs ?

We had never left Go Discs. Must be a French thing, this.

Why did you produced yourselves with album ?

We didn’t make a conscious decision to self-produce, we just accumulated a lot of songs through days and nights taping songs in Shabby Road. They were mostly well-recorded, as by this time, we were quite au fait with the studio and had an excellent in-house engineer, Larry Primrose, and we were always in there – either the whole group, or in ones and twos. There was no need to call in anyone until the songs reached the mixing stage, at which point our enthusiastic amateurishness became a liability. We mixed some songs with Cenzo Townshend and some with Steve Whitfield, both of whom came up to work in Shabby Road, and some others with Hugh Jones, who took us down to the Wool Hall in Bath to work through the summer, for which I’ll always be grateful.

How did you find the sound of this album ?

There’s a lot of dulcimer and 12-string acoustic guitars chiming throughout, but the record doesn’t ‘jangle’ at all. The sonics seem a bit threatening and claustrophobic instead, and a bit stifled – I like that about it. Sums up my memory of the group mood at that time: broody, wary of staleness incoming, stoned.

What’s your best memories about this recording process ?

The time at The Wool Hall was really lovely. England in the summertime, when they have a summer, is so beautiful. We weren’t really needed all that much in the studio because it was mostly a mixing session, so i walked around the village, saw some Morris Dancing in the pub, scored some bootleg Scrumpy cider. I drank a lot actually, but I also went to evensong at the local church, so that’s ok. It was like being back in the 1930s, without the period-drama murder mystery (though we came close) or the real-life drama of impending war.

What’s your favorite A Happy Pocket song ?

I like the instrumental, ‘Outside’. I’d always much rather hear instrumental version of our songs, actually. I also still like ‘The Genius I Was’ – I’m fond of anything that drones, apart from drones themselves. And who couldn’t love Paul singing ‘I Must Fly’? ‘Safecracker’ is another excellent one.

Weightlifting

How did you meet Simon Dine ?

We go back a long way. All the way back to your first question, in fact. He was on tour with The Lilac Time in about 1988, and saw us play support in Edinburgh and Dundee. We was responsible for us being signed to Go Discs, where he continued to work closely with us as our label contact for the rest of his time there. He left before A Happy Pocket came out, I think. By that time, he and I had grown to be close friends, and when he started to move into making his own music (with Noonday Underground), I really liked what he was doing and asked him up to Shabby Road to work on mixing his first album, ‘Self Assembly’ with him. Then I wrote and sang on a couple of songs on his next album, ‘Surface Noise’. So he has completed two or three albums by the time we get round to making Weightlifting, and I just asked him to try and work his magic on a couple of our tunes. More about Simon Dine later…

Norman Blake (Teenage Fanblub) sang on Got Carried Away. What are your influences on Weightlifting ?

It’s hard to say specifically what music was influencing us 15 or so years ago, but i do remember the pervading feeling of determination, having come through a messy but merciful divorce with the major label and realizing there was plenty of resilience among the songwriters. It was great to know we could still delight each other.

Why did you deal with SpinART Records ?

Our manager at the time found them, and it seemed like a good match. Unfortunately, it wasn’t. We’re still most of the US sales royalties due to us for Weightlifting, but we’ll never see them.

How did you write your songs ? Did you use the same method singe the beginning of the band ?

Some aspects of the process are the same as they’ve always been. Paul and I write quite a lot together, as do Davy and I. John tends to write more on his own. Having said that, we are all aware of what songs are in need of ideas, and all of us will chip in with opinions, suggestions. All this used to be done face-to-face, and now it’s over email (Paul and I are in the US, John and Davy are in Scotland). That change has slowed things up, but it’s the way it has to be.

And why did you call your band The Trashcan Sinatras ?

The old story is that the original four-piece who first played as TCS were myself and Davy Hughes, plus George McDaid (who played bass on Cake) and a drummer called Paul Forde. We met each other on a week-long course of vocational classes/meetings for unemployed teenagers, and one of the activities they had everyone doing there involved putting on a show of some sort. We four were all into music – the other three were already in bands, though I wasn’t – and so we decided to make our contribution a musical performance using what we could find in the trash. We gathered up things to hit, things to blow into (after cleaning them), and Davy sang a Frank Sinatra song over the top. Paul Forde came up with the name, and when the four of us decided to play a real gig a few months later, we stuck with it. The band evolved quite quickly, and I think we grew into the name musically, in the sense that we always enjoyed combining our punkier inclinations with our collective love of Tin Pan Alley.

In The Music

How did you meet Andy Chase ? And Carly Simon ?

Andy had got in touch offering to mix the Weightlifting album. He did a great job on that, and we talked then about doing the next one together from the start, and 4 years or so later, we had enough good songs to head over to his studio in New York City. Carly was/is a neighbour of Andy’s on Martha’s Vineyard, where we recorded the vocals for the album. Finding out we had a connection to the great Carly Simon, of course we wanted to persuade her to sing on the record, so John wrote her a letter asking, enclosing a tape of a few songs. Fantastically, she said she was really into a song of John’s called Should I Pray – a big thrill for us, John especially. We didn’t get to meet her, unfortunately. That would have beee asking too much.

What’s the story of Morning Star ?

I just had a listen there, to see what came back. I think Paul’s music is really great, but i’m not that keen on the words i came up with, or with my singing. The whole ITM album was coloured with happiness, which i found difficult to express properly, being a bit of crabbit bastard (‘crabbit’ is Scottish for ‘complaining’). I tried to wrote something about having just met my now-wife. It came out a little clumsy, I think. Not a favourite.

How easy was the recording process of this album ? What’s your most difficult recording process ?

I think this one was pretty much a delight from start to finish. We had a guy called Grant playing very bubbly bass, Stevie – who is still with us today – on keys, and a friend called Jody on extra guitar, so we could play the backing tracks live. We all decamped to the lower west side of Manhattan, to Andy Chase’s studio, and had a blast. Long days meandering in and out of the chords and rhythms, and long, late nights in New York’s finest dive bar – called ‘Dive Bar’ – piling money into the juke box.

Well, nothing beats Shabby Road, but most any recording set up is fine if you have the songs. The recording sessions i shudder to remember are all those where we were in there too early and tried to eke the songs out. Oh, and home recording is a drag now that it’s all pointing and clicking.

You supported the 2009 album release with nearly 40 concerts and promotional appearances in the United States, Japan and the United Kingdom… What’s your favorite memory about this tour ?

There are certain places in the US where the crowd tend to be boisterous and into the fun of it all. St. Louis and San Francisco come to mind. Detroit, too. Japan is always wonderfully strange. One highlight was learning a song of ours in Japanese and having our friends from Tokyo’s Sunny Day Service join us onstage to play along, and to laugh at my strangled phonetics.

Wild Pendulum

It’s your best album. I’m wrong ?

I think you might be right. It’s certainly my favourite.

What’s the story of the song All Night ? SHE IS VERY VERY VERY AMAZING!

It started as a rather plaintive and pretty song, with John writing a chorus and Davy and me helping with the verses. From my point of view, I was thinking about how a large number of the old and splendid churches in Glasgow seemed to have ended up being converted into nightclubs, and so the idea of the DJ in the pulpit, saving us all, took hold. I think Jesus would approve. We sent it to Simon Dine to see if he fancied adding a few of his special orchestrations, and he came back with what you hear – Herb Alpert’s ‘Lonely Bull’ and all. More about Simon Dine later…

Your new sound is fantastic. How did you find it ?

Ah, well there was this fellow called Simon Dine you see – you might have heard of him. He was an old friend of ours from way back at question 1. He had been our A&R man at Go Discs and had moved onto making and producing these wonky, wonderful sonic crystal palaces of his own, and he and I had been thinking about doing a record together, after all the touring for ITM was done. Meanwhile, when it came time for the group to gather our energies for another haul up the mountain of album-making, we found we didn’t have the drive to work on songs in any of the ways we were used to. So I started listening to Simon’s latest batch of ideas – these fantastic and inspiring pieces he’d constructed that were really deserving of more than i could offer on my own – and I suggested the whole group of us got together and made this record with Simon. We had a few songs of our own that we fed to Simon for embellishment, but most of the songs on WP started as instrumentals from him that easily evoked all sorts of moods to us as writers: Vaudeville, cowboy desert soundscapes, stormy sixties balladry, powdery psychedelia, and we added chords, new sections, found lyrics that could do justice to the sounds. It all took a while, and we ended up with all these pretty jagged and frayed demos that we all felt needed an outside authority to come in and pull them together into the slick jaw-droppers we knew they could be. One or two other producers ran away screaming from us when we presented the demos, but Mike Mogis of Bright Eyes thought it all sounded bizarre and would be great fun to work on. He brought along Nate Walcott from his band, who played keys and arranged all the strings. Off we all went to Mike’s studio in Nebraska and it worked like a charm. Between Simon and the two Bright Eyes guys, we couldn’t have wished for better collaborators and a lot of the credit for the sound of the record goes to them.

This album was published by Pledge Music. What did you think about the crowdfunding ?

We did a form of crowd-funding for ITM too, but in the 5 years or so after that record, it became a much more established way to raise money for recording, manufacturing and promoting music. It keeps you on your toes to have the fans involved from the start – i think it’s healthy. I wish it wasn’t necessary, but c’est la vie.

How did you choose the team of the recording process ( Howie Weinberg, Christopher Thorn) ?

Those two were actually minimally involved compared to Mike Mogis, Simon Dine and Nate Walcott. They are experts in their own fields though, of course. Howie is a mastering engineer of great renown, and Christopher kindly allowed me to come to his lovely, twinkly studio in Laurel Canyon to repair a couple of vocal lines I’d fucked up in Nebraska.

Keep (on) Dancing Inc. until the end

Keep (on) Dancing Inc. until the end Albin de la Simone est l’un des notres

Albin de la Simone est l’un des notres

So much talent and humility. Amazing band.

Yes !

Merci pour cette itw de ce groupe affreusement sous-estimé et bien trop discret (surtout par ici).

Merci de votre retour !