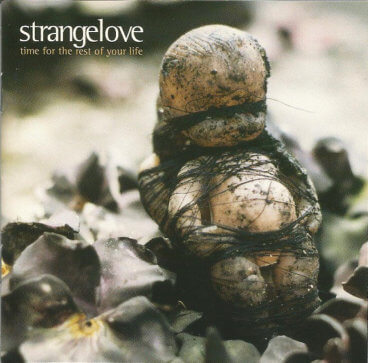

En 1994, Strangelove publie un premier album (Time for the Rest of Your Life) qui échoue aux portes du Top 50. Il faut dire qu’à l’époque, la concurrence est rude. Bloqué entre Oasis et Pulp, Strangelove sera le petit frère chéri de Suede et le groupe préféré des gens lettrés (dont Radiohead fait évidemment partie). Retour sur l’enregistrement de Time for the Rest of Your Life, le diamant noir de la pop anglaise des 90’s avec Patrick Duff et Alex Lee. Vingt-cinq ans après sa sortie, ce disque est toujours un bonheur à écouter.

Strangelove venait de Bristol. Le groupe est une savante addition de la scène de cette ville. On retrouve dans ce groupe des membres de The Blue Aeroplanes et des anciens Jazz Butcher. On retrouvera, après la séparation du groupe en 1998, des Strangelove derrière Baxter Dury (pour la tournée du fantastique Len Parrot’s Memorial Lift) et Alex Lee à la production des disques solos de Duff. De 1992 à 1998, Strangelove va produire trois albums sombres comme de la poix qui vont éclairer les laissés pour compte de la brit pop.

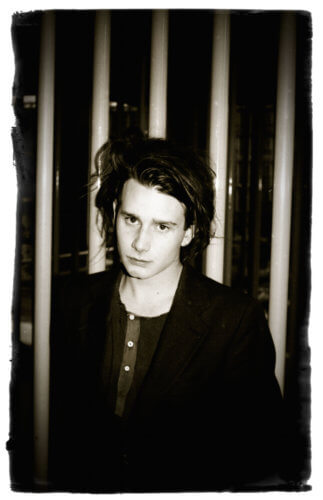

Patrick Duff

Patrick Duff était le chanteur de Strangelove. Après la fin du groupe, il a publié des disques solos. Leaving My Father’s House, son nouveau disque, est annoncé pour les prochaines semaines.

Comment vous-êtes vous retrouvés sur le label Food (Blur) ? Pourquoi avoir signé avec eux ?

Patrick Duff : Nous jouions au Marquee et c’était notre sixième concert. Il y avait trois groupes ce soir là et nous étions les premiers. Juste avant, nous étions coincés dans un embouteillage londonien pendant des heures et nous sommes arrivés sur les lieux environ dix minutes avant le début de concert. Nous n’avons pas pu faire les balances. Nous n’avons donc joué que six chansons et je suis resté la tête baissée pendant tout le concert. L’équipe de Food était là pour voir la tête d’affiche mais Dave Balph a décidé de nous signer à la place. Une semaine plus tard, nous sommes allés à Londres et nous avons rencontré Dave et Andy Ross. Dans l’après-midi, nous devions signer mais ils étaient assez inquiets quant à ma gestion de la scène. Je n’avais pas l’air à l’aise sur scène selon eux. Je leur ai dit que je ne voulais pas particulièrement avoir l’air à l’aise. Ils ont tous deux dit que c’était une bonne réponse à laquelle ils ne s’attendaient pas. Après ça, nous sommes allés nous saouler avec Blur et plus tard, le guitariste des Buzzcocks a voulu se battre à l’hôtel Columbia, mais Joe s’est interposé et lui a dit de partir.

Pourquoi avoir travaillé avec le producteur Paul Corkett ?

Paul avait travaillé sur Jehovakil de Julian Cope et nous avions tous adoré ce disque. De plus, Paul était le seul producteur qui n’avait pas énervé Alex. Paul était vraiment un bon gars. Il était calme, sensible et aimait vraiment la musique. Son épouse, Rachel, avait une présence très douce et apaisante dans le studio, tout comme le chien de Paul, Harry, un labrador noir. L’animal le plus calme que j’ai jamais vu. Historiquement, c’est le chien qui a le plus fumé (de manière passive).

Comment s’est passé l’enregistrement ?

Paul avait un tableau noir avec toutes les choses que nous devions écrire. Peu à peu, nous les avons toutes réalisées les unes après les autres. A chaque fois que nous faisions une des choses de la liste, il l’effaçait. C’était bon de voir les mots à la craie disparaître et se transformer en musique. La musique a été facile à faire même si nous étions rarement tous réunis.

Combien de temps cela vous a pris ?

Quelques semaines.

Et quels sont tes meilleurs souvenirs liés à l’enregistrement de ce disque ?

Nous enregistrions dans aux studios Jacob qui se trouvaient à la campagne. J’habitais dans le centre-ville de Bristol, c’était donc c’était cool d’être en pleine nature. Le reste du groupe m’a gentiment laissé la meilleure pièce de la maison et je peux encore me souvenir des hiboux derrière la fenêtre de ma chambre… Ces hiboux dans les arbres me parlaient tous les soirs. Je jure qu’à l’époque je savais ce qu’ils essayaient de me dire mais que je ne pourrais pas l’expliquer correctement avec des mots.

On pouvait aussi entendre les petits oiseaux le matin. C’était étrange parce que le calme était très intense et il n’y avait pas de bruit de la circulation. Je me suis couché tard tous les soirs en studio pour jouer du piano à queue. Parfois, le guitariste de Napalm Death, qui enregistrait dans le studio voisin, venait m’encourager et m’inciter à prendre de la drogue avec lui et à jouer de la guitare acoustique. Nous restions alors éveillés toute la nuit. Nous faisions des jams lents et assez complexes sur lesquels j’inventais des mots absurdes. Ça le faisait se tordre de rire.

Un matin, je me suis réveillé à l’aube, malade comme un chien et tremblant d’anxiété, comme d’habitude. J’ai marché aveuglement dehors dans un champ à côté de la maison. Soudain, mon cœur battait à tout rompre et, surpris, j’ai levé les yeux du sol où mes yeux s’attardaient le plus naturellement à l’époque. Un énorme lièvre courait vers les collines. Le son de ses pieds sur la terre a résonné dans tout mon corps. Dans l’intensité de ce moment, j’ai réalisé que le lièvre m’avait volé quelque chose. Je l’ai regardé s’enfuir à l’horizon. J’étais perplexe au-delà de toute imagination, me tenant là, complètement choquée, impuissante et terrifiée. Le lièvre avait volé un morceau de mon âme. Je sentais des larmes amères monter dans mes yeux. Cependant, maintenant, toutes ces années plus tard, je réalise que ce n’était pas un vol. Ce lièvre s’est simplement occupé de moi et a gardé ce morceau en sécurité le temps que je vienne le récupérer.

Après le départ de Napalm Death, The Cure a occupé le studio voisin. Je n’oublierai jamais l’arrivée des Cure au studio. Je vois encore apparaître les cinq jeeps noires identiques. Elles descendirent l’allée longue l’un derrière l’autre en conduisant au ralenti. J’ai regardé ce court moment qui m’a semblé duré des heures.

Paul qui se tenait derrière moi a soudainement déclaré: « C’est The Cure !». Ces mots m’ont transpercé comme un fil d’or. Il n’y avait pas Internet à ce moment-là, donc voir de vraies pop stars qui venaient vers toi dans des jeeps était un moment assez étrange. Ce moment est resté à jamais gravé dans ma mémoire.

Cette nuit-là, Paul et moi sommes allés dehors et nous avons traversé le jardin jusqu’à leur studio. Paul m’a soulevé pour que je puisse regarder par la fenêtre. Nous étions sortis de notre studio et je voulais voir ce qu’ils faisaient parce que j’ai aimé The Cure depuis mon enfance. Je les aime toujours d’ailleurs. L’éclairage était sombre et nous avons vu que leurs masses de cheveux. Paul n’a pas réussi à me porter et nous sommes tombés. Ils ont alors arrêté de parler et on essayait de voir ce qu’ils se passait. Nous sommes restés là pendant des heures en priant pour qu’ils ne viennent pas à l’extérieur et en essayant de ne pas rire, même si cela nous faisait très peur. Qu’est-ce que j’aurais dit ? Curieusement, Paul les a produits quelques années plus tard.

Deux jours après cette nuit désespérée, je suis entré dans la grande cuisine commune au rez-de-chaussée et j’ai pris une bouteille de vin. À mon insu, j’avais pris la bouteille de Robert. Apparemment, il n’a pas été choqué outre mesure. Je me sentais tellement mal à ce sujet. J’aurais aimé me lier d’amitié avec eux, mais à l’époque, je n’avais pas réalisé qu’on pouvait parler à des stars. Nous aurions probablement pu finir par faire leurs premières parties mais je n’avais pas une ambition démesurée.

Je me souviens d’Alex qui avait doublé la guitare d’intro à Is There A Place. Nous étions tous dans la salle de contrôle avec lui pendant qu’il y jouait. Ce fut un moment musical étonnant. C’était en pleine nuit à la fin de l’enregistrement. À ce stade du processus, la situation était hors de contrôle. Nous étions tous réunis et nous avons littéralement applaudi pendant qu’il le faisait parce que ça sonnait vraiment bien. C’était absolument exaltant de faire partie de quelque chose d’aussi indiscipliné et de créatif. Il y avait tellement de talent dans ce groupe que c’était fou. Quelle vie !

Tu as des regrets concernant ce disque ?

Je ne l’ai jamais écouté, mais je me souvenais que j’avais voulu, à l’époque, avoir un chant plus fort… Mais j’étais trop timide et je manquais de confiance…

Alex Lee

Alex Lee fut le guitariste de Strangelove. Après la dissolution du groupe, il a intégré Suede le temps du splendide A New Morning. Il a ensuite travaillé avec Placebo et Goldfrapp.

Comment s’est déroulé l’enregistrement de ce premier album ? Quels sont tes meilleurs souvenirs le concernant ?

Alex Lee : Strangelove a eu du mal à reproduire la magie intangible qui régnait pendant ses concerts. Comme beaucoup de groupes qui débutent en studio… C’est peut être difficile de capturer l’intensité et l’esprit qui unit cinq personnes sur la scène une fois que la magnétophone tourne et que le public n’est pas là. Dès ses débuts Strangelove a tenté de retrouver sa part sombre avec des producteurs qui avaient un immense CV et qui avaient réalisé de grands albums. Mais il était difficile de traduire notre monde de la scène à la studio.

Nous avons ensuite enregistré notre deuxième single, Hysteria Unknown, avec le producteur Donald Ross Skinner (guitariste de Julian Cope) et l’ingénieur Pete Jones. Le single semblait fantastique et le label pensait que nous avions trouvé l’équipe idéale. Notre label de disques, Food, n’était pas convaincu. Plus précisément, Dave Balfe, qui nous a signés, n’était pas satisfait et souhaitait que nous continuions à chercher un autre producteur. Donald a recommandé Paul Corkett qui avait été auditionné en remixant la chanson Time For The Rest Of Your Life. Il a obtenu le contrat. Toujours vêtu de noir et fumant cigarette sur cigarette, il était aussi pâle que quelqu’un qui pensait clairement que la lumière du jour était surestimée. Nous avions trouvé notre homme. C’était comme avoir un autre membre du groupe et Paul a travaillé avec nous sur nos trois albums.

Après autant de nos faux-départs pour réaliser notre premier album, je pense souvent que les enregistrements les plus honnêtes de Strangelove de cette époque ont été pris lors de nos concerts. La Black Session enregistrée à Paris en octobre 1994 en est un bon exemple. Ce type de performance nous a échappé en studio, quelle que soit la qualité de nos efforts. Cependant, je garde des souvenirs incroyablement chaleureux de notre temps aux Jacob Studios une maison de campagne située l’idyllique Surrey.

Ce studio étaot à la pointe de la technologie et il possédait une atmosphère d’un autre monde. Nos séances d’enregistrement se faisaient la nuit. Cela nous permettait d’échapper aux distractions de la ville et de nous immerger totalement dans l’enregistrement.

Il y avait un autre studio à côté du nôtre et nous avons eu quelques voisins légendaires pendant le mois de notre enregistrement. Au début de la session, Napalm Death se trouvait juste dans le studio voisin. Et c’est The Cure qui a occupé ce même studio à la fin de nos sessions. Ils travallaient avec un producteur dont le nom m’échappe. Il travaillait sur un remix de Femme Fatale du Velvet Underground par Duran Duran. Il m’a demandé de jouer de la guitare dessus, estimant qu’il lui fallait «quelque chose de plus». J’ai accepté volontiers même si ce n’étai pas ma tasse de thé. J’ai pris ma Gibson 335 et mon pédalier dans la salle de contrôle et il a commencé à jouer la chanson sur les gros haut-parleurs. Fier de ma filiation velvetienne, j’ai voulu me venger de Duran Duran. Ma soeur les avait beaucoup écoutés quand j’étais jeune. J’ai décidé d’adopter une approche de la guitare déconstructionniste avant-gardiste. Très légérement… Je me suis mis à faire des bruits industriels atones que même Lou Reed refusé de mettre sur Metal Machine Music. Après une quinzaine de minutes, le producteur m’a fait sortir du studio très poliment mais fermement et, sans surprise, ma prise de guitare a été refusé

Ce disque est sorti en 1994 et a reçu un très bel accueil de la part des médias. Mais ce fut un échec commercial.Ce fut une déception pour toi ?

Personnellement, je n’attendais aucun succès commercial. Notre son était complètement différent du reste de la scène musicale de cette époque. Nous espérions que les bonnes chroniques et le soutien de John Peel et de Bernard Lenoir nous attireraient un public plus grand. Et puis nous avons publié Is There A Place ? comme single. Qu’attendre d’un single qui fait onze minutes ?

Strangelove – Is There A Place?

Te rappelles-tu de votre premier concert français ? Il a eu lien à Orléans en 1993. ET te rappelles-tu de cette fameuse Black Session ?

Orléans fut en effet l’un de nos premiers concerts à l’étranger. Je me souviens d’avoir conduit de Bristol à Orléans avec une seule cassette dans la camionnette, Revolver des Beatles. Elle était totalement usée quand nous sommes revenus à Calais.

Pour être honnête, je ne me souviens pas beaucoup de cette tournée. Par contre, je me rappelle du retour incroyable du public. Il y avait un vrai lien avec le public français. Ce dernier nous a soutenus jusqu’à notre dernier concert à Bourges en 1998. Nous avons énormément apprécié cet amour.

Strangelove venait de Bristol. C’était quelque chose d’important pour vous ?

Oui. Bristol était assez proche de Londres pour faire avancer les choses, mais assez loin pour pouvoir respirer.

As-tu des regrets concernant ce disque ?

Vingt-cinq ans est une période trop longue pour susciter des regrets à propos d’un album. Mes sentiments à son égard se sont adoucis au fil du temps et lorsque je l’écoute, je le trouve imparfait mais il une qualité romantique qui perdure encore. Nous aurions peut-être dû mettre Hysteria Unknown dessus et j’aurais aimé prendre plus de temps pour améliorer le mixage, mais nous avions tellement dépensé le budget consacré aux sessions avortées qu’il était difficile de discuter avec le label. . Je pense que notre deuxième album Love And Other Demons est probablement un meilleur album, mais Time For The Rest Of Your Life résiste encore au temps qui passe.

Strangelove – Sixer

Quelle est l’histoire de Sand ? C’est ma chanson préférée de ce disque. Et toi ? Quelle chanson préfères-tu ?

Sand a été écrite par Patrick et David Francolini, notre premier batteur. Ils avaient enregistré une démo dans une chambre qui possédait ce riff cyclique hypnotique réglé sur un rythme ultra rapide. J’ai adoré la double voix de Patrick avec des harmonies qui la rendaient rêveuse et abstraite malgré le tempo maniaque. J’ai pensé qu’un changement de vitesse pourrait être intéressant. J’ai donc ajouté une partie de guitare brutale au milieu pour sortir l’auditeur de la transe. Ce fut l’une des premières collaborations qui m’a convaincu que nous devions faire un groupe.

J’ai un faible pour I Will Burn. Elle a été enregistrée à la toute fin de la session au Jacob Studio. C’est le son du soleil qui se lève à Jacobs Studio.

Strangelove - Time For The Rest Of Your Life

Time For The Rest Of Your Life des Strangelove est disponible chez Food/EMI.

- Sixer

- Time For The Rest Of Your Life

- Quiet Day

- Sand

- I Will Burn

- Low Life

- World Outside

- The Return Of The Real Me

- All Because Of You

- Fire (Show Me Light)

- Hopeful

- Kite

- Is There A Place?

Les photographies de cet articles sont signées Sébastien Faits-Divers. Elles sont sa propriété.

Merci à Sébastien FD et Christophe B. pour les précieuses informations.

English text

Patrick Duff

How did you meet the team of Food ? Why did you choose to a deal with Food ?

Patrick Duff : We were playing at the Marquee. This was our sixth ever gig. It was a three band bill and we were the first on. Just before we had been stuck in a London traffic jam for hours and arrived at the venue about ten minutes before we went on, didn’t even get a soundcheck. We only played six songs and I just stood there with my head down through the whole gig.

Food were there to see the main band but Dave Balph decided he wanted to sign us instead.

A week or so later we went to London and we met Dave and Andy Ross. That afternoon I remember them saying they wanted to sign us but the only thing they were worried about was that I didn’t look comfortable on stage.

I told them that I didn’t particularly want to look comfortable. They both said that was a good answer that they weren’t expecting.

Then we got drunk with Blur and later on the guitarist of the Buzzcocks wanted to beat me up in the Columbia hotel but Joe got between us and told him to back off. It was all pretty good natured rock n roll nonsense really I now realise.

Why did you choose to work with Paul Corkett ?

Paul has worked on Julian Cope’s album Jehovakil and we all loved that record. Also Paul was the only producer we’d met up to that point who didn’t piss Alex off.

Paul was such a great guy. Quiet and sensitive and totally loved music. His wife Rachel was a really kind soothing presence in the studio too as was Paul’s dog Harry, a black Labrador. The calmest animal I’d ever witnessed. He had passively breathed in more smoke than any dog in dog history.

How easy was this recording process ?

Paul had a blackboard with all the things we had to do written on it. Gradually we did all of them one at at time. Each time we did something it got rubbed out and then it was done. It was a good feeling watching the chalk words disappearing and turning into music. We were all out of it most of the time so that part of it was difficult but the music was easy.

How did long it take you ?

A few weeks.

What are your best memories of this recording process ?

We were recording in a studio called Jacob’s way out in the countryside. I lived in the city centre of Bristol so it was cool to be away in nature. The rest of the band kindly let me have the best room in the house and I can still remember the owls outside my bedroom window.. Those owls in the trees were talking to me in particular every night. I got to know what was going down and I swear at the time I knew what they were trying to tell me but couldn’t explain it properly in words.

You could hear the small birds in the morning too. It was eerie because the stillness was so profound and there was no sound of traffic. I stayed up late each night in the studio playing on the grand piano. Or the guitarist of Napalm Death, who were recording in the adjoining studio, would come over and encourage me to take drugs with him and play on the acoustic guitars. We’d stay up all night. Slow intricate jams with me making up nonsense words. He’d be rolling around laughing.

One morning I woke up at dawn sick as a dog and shaking with anxiety as usual. I blindly made my way outside into a field beside the house. Suddenly there was a great pounding in my heart and startled I looked up from the ground where my eyes most naturally lingered back then. A huge hare was running for the hills. The sound of it’s feet on the earth reverberating through my whole body. In the intensity of that moment I realised the hare had stolen something from me. I watched it running away to the horizon. I was confused beyond imagination standing there utterly shocked, powerless and terrified. The hare had stolen a piece of my soul. I felt bitter tears rising in my eyes.

However now all these years later I realise it wasn’t a theft. That hare was only looking after it for me and keeping it safe until the day I was ready to have it back again.

After Napalm Death left The Cure came to the other studio next door. I’ll never forget standing there completely out of my mind and watching them turn up in five identical black jeeps. They came down the long driveway one behind the other driving in slow motion. I watched for what felt like hours.

Paul who was standing behind me suddenly said “ That’s The Cure” . Those words went through me like a golden thread. There was no internet back then so seeing actual pop stars coming towards you in jeeps was weird enough as it was even if you were straight and the image is burnt into my retina.

That night me and Paul went outside and sneaked through the garden up to their studio. Paul lifted me up so I could look through their window. We were out of it and I wanted to see what they were doing because I’d loved The Cure when I was a kid. Still do. It was gloomy lighting and a load of crimped hair and then Paul couldn’t hold me anymore and we both fell over. You could hear they’d stopped talking and were trying to work out what was going on. We lay there for ages praying they wouldn’t come outside and trying not to giggle even though it was pretty scary. What would I have said ? Funnily enough Paul went on to produce them a few years later.

Two days after that one night desperate I stole into the large communal kitchen downstairs and took a bottle of wine . Unbeknownst to me it was ‘Robert’s bottle’. Apparently he was not particularly impressed about that. I felt so bad about it . I wish I’d just made friends with them instead but back then I didn’t realise you were allowed to talk to pop stars. We probably could have ended up supporting them or something like that if I’d had any sense or even a jigger of ambition.

I remember Alex over dubbing the intro guitar to Is There A Place . We were all in the control room with him whilst he was playing it. This was an amazing musical moment. It was in the dead of night and right at the end of the recording process. We were all so far gone by this point in proceedings that it was now basically out of control. But it all came back together that night and we were all literally cheering while he did it because it sounded so fucking cool. It was utterly exhilarating to be part of something so unruly and so creative. There was so much talent in that band it was insane. So much vitality.

Do you have some regreats about this record ?

I haven’t ever listened back to it but I remember at the time I wanted the vocals to be louder but was too shy and lacking in confidence to say so.

<2>Alex Lee

How easy was, for you, the recording process of this first Strangelove record ? What are your best memories of this recording process ?

Alex Lee : Like many young bands in the recording studio, Strangelove found it hard to reproduce that intangible magic that we had at our live shows. Capturing the intensity and spirit that connects five people onstage can be elusive once the tape machine is rolling and the audience is missing. In the early days of Strangelove, we had many attempts at this dark art with several different producers, all of whom had great track records and had made successful albums for other bands, but it was a struggle to translate our world from the stage to the studio.

We then recorded Hysteria Unknown, our second single, with producer Donald Ross Skinner (Julian Cope’s guitarist) and engineer Pete Jones. The single sounded fantastic and the band thought we had the dream team. Our record label Food wasn’t convinced though. More specifically Dave Balfe, who signed us, wasn’t happy and he wanted us to keep looking for another producer. Donald recommended Paul Corkett who auditioned by remixing the song Time For The Rest Of Your Life & he got the gig. Always dressed in black and a proper chain-smoker, he wore the pallor of someone who clearly thought daylight was overrated. We’d found our man. It was like having another member of the band and Paul worked with us on all three of our albums.

After so many false starts in the making of our first album, I often think the most honest recordings of Strangelove in that era were taken from our live shows. The Black Session recorded in Paris in October 1994 being a good example. There’s an intensity and cohesion in that performance that escaped us in the studio no matter how hard we tried. However, I have incredibly fond memories of our time at Jacobs Studio, a country mansion in idyllic rural Surrey that was named after the local breed of sheep. Jacobs had a state of the art studio and an other-worldly atmosphere which, as our sessions were strictly nocturnal, gave us a chance to escape the distractions of the city and immerse ourselves in the recording.

There was another studio next to ours at Jacobs and we had some legendary neighbours during our month there. At the start of the session Napalm Death were next door & The Cure moved in towards the end. Sandwiched between them was a producer, who’s name I forget now, working there alone remixing a Duran Duran cover version of Femme Fatale by The Velvet Underground. He asked me to play some guitar on it as he felt it needed “something extra”. I was a little worse for wear but willingly agreed. I took my Gibson 335 and pedal board into the control room and he started playing the song on the big speakers. Being fiercely proud of my allegiance to the Velvets and using it as an opportunity to get revenge on Duran Duran, who had been played to death by my sister throughout our adolescence, I decided an avant-garde, deconstructionist guitar approach was required to rough it up a little. I proceeded to make unlistenable, atonal industrial noises that even Lou Read would have rejected on Metal Machine Music. After about fifteen minutes, the producer very politely but firmly ushered me out of the studio and unsurprisingly my guitar takes failed to make the cut.

Time for The Rest of Your Life was released in August 1994, to critical acclaim. This record was a critical success but not a commercial success. It was a huge disappointment for you?

Personally, I never had high expectations of commercial success as I thought our sound was completely out of kilter with the rest of the music scene at that time. We hoped that some good press and support from the likes of John Peel & Bernard Lenoir would bring us a wider audience. And we did release Is There A Place? as a single which is about eleven minutes long so what could you really expect?

Do you remember you french first show (Orléans – 1993) ? Do you remember the Black Session ?

Orléans was one of our first gigs abroad and I remember driving there from Bristol with only one cassette in the van, Revolver by the Beatles, that we wore out by the time we got back to Calais.

I don’t remember much about the set to be honest but I do remember the response from the crowd which was incredible and that started a kinship with French audiences until our final ever gig in Bourges in 1998. We always had great support wherever we went in France and genuinely appreciated their warmth towards us.

Strangelove came from Bristol.. It was important for you ?

Yes. Bristol was close enough to London to get things done but far enough away to still breathe.

Do you have some regrets about this record ?

Twenty five years is too long to harbour major regrets about an album. My feelings towards it have softened over time and when I listen back to it now, I know it’s flawed but it has a doomed, romantic quality that still endures. Maybe we should have put Hysteria Unknown on it and I wish we’d taken more time to make the mixes better but we’d blown so much of the budget on aborted sessions at the start that it was a hard case to argue with the label. I think our second album Love And Other Demons is probably a better record but Time For The Rest Of Your Life still stands up pretty well.

What’s the story of Sand ? It’s my fav’ song of this record. And you ? What’s your fav’ song of this record ?

Sand was started by Patrick and David Francolini, who was our first drummer. They had recorded a bedroom demo of it that was this hypnotic, cyclical riff set to a super fast motorik beat. I loved Patrick’s double vocal with harmonies all the way through which somehow made it dreamy and abstract despite the manic tempo. I thought it could take a shift up to another gear so I added the brutal guitar section in the middle to shake the listener out of the trance. It was one of the early collaborations that convinced me that we were meant to be in a band together.

I also have a very soft spot for I Will Burn. We always worked on it at the end of the session so to me it’s the sound of the sun coming up at Jacobs Studio.

C’est reparti pour un tour avec Eiffel

C’est reparti pour un tour avec Eiffel L’envol de Minuit Avant La Nuit

L’envol de Minuit Avant La Nuit